From vision to action

a decade of analysis, disruption and resilience

September 2023 marks the 10th anniversary of the founding of the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime.

This is an opportunity to not only look back and reflect on 10 years of the work of the GI-TOC in responding to the challenges and harms of transnational organized crime, but, more importantly, to recognize that much still needs to be done.

The threat and complexity of organized crime facing the world today are arguably more menacing than ever before, and it is critical to understand those threats and plan strategically for a coordinated global response for the next 10 years.

Anniversary statement by the GI-TOC Director, Mark Shaw.

2013

A new vision is conceived

The seeds of the GI-TOC, however, can be traced back a little further to 2009, when the International Peace Institute in New York published a paper, ‘Transnational Organized Crime’.

Ten years ago, the GI-TOC was conceived as a platform to assess the extent of, and determine more effective responses to, organized crime. The seeds of the GI-TOC, however, can be traced back a little further to 2009, when the International Peace Institute in New York published a paper, ‘Transnational Organized Crime’. The report advocated for a rethink of international approaches to counter organized crime and for a conference to be convened in 2010 to coincide with the 10th anniversary of the signing of the Palermo Convention (UNTOC).

The paper drew attention to the changing nature of transnational organized crime and the increased global security threat it posed

The paper, which was written after consultations with the Italian and Mexican missions to the UN, put forward the need to strengthen political commitment to developing new global strategies to address the growing problem. It drew attention to the changing nature of transnational organized crime and the increased global security threat it posed. It was at the time becoming apparent that new thinking around organized crime was beginning to germinate, as well as the need to rally a broad corpus of international cooperation to help the initiative take root and make it practicable.

Those early stages of the development of an ‘initiative’ that flowed from the embryonic projects spearheaded by the IPI and others rapidly gained momentum

There ensued a series of consultations among senior law-enforcement officials, practitioners and analysts concerned about the growing impact of organized crime and dedicated to finding better ways of dealing with it. These meetings, facilitated by Peter Gastrow, then a senior fellow of the International Peace Institute, would eventually culminate in the formal launch of the GI-TOC. Those early stages of the development of an ‘initiative’ that flowed from the embryonic projects spearheaded by the IPI and others rapidly gained momentum, leading to a meeting in February 2012 where a founding statement was drafted and adopted by the participants, who would become the founding members of the GI-TOC.

Countering organized crime could no longer be the mandate of law enforcement agencies alone

During that preparatory meeting, broader strategies that reached beyond reshaping law enforcement cooperation, such as the impact of organized crime on development, were identified as fundamental if the new initiative was to see the light of day. It was the very framework for addressing organized crime itself that needed to be reshaped. To achieve this, the participants envisaged that the new initiative should entail a more inclusive scope, that countering organized crime could no longer be the mandate of law enforcement agencies alone – it needed to elicit consensus among governments, multilateral organizations and the private sector, and, crucially, engage civil society in the form of NGOs, academia and the media. A whole-of society approach would be needed.

The founding document:

‘A Network to Counter Networks’

The founding document, which articulated why the organization came into existence, set out the objectives of the new Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime and the steps to be taken in the response.

Ten years later, this pivotal document still encapsulates the essence of the GI-TOC’s approach, even though the landscape of organized crime has mutated considerably over the decade, necessitating flexibility and adaptation along the way. The document laid the foundations that would propel the initiative forward for the next decade of impacting policy coordination around organized crime.

The objectives set out in the document highlighted the challenges of globalization, which had, in tandem, accelerated the global reach of criminal economies since the 1990s; how criminal opportunism had harnessed rapid technological development; that policing systems needed to adapt and cooperate more effectively; that there was an urgent need to build more effective political consensus and mobilize a more strategic global approach to what had taken the form of an increasingly global threat to stability.

The concept of the GI-TOC was to mobilize a wider group of expertise, to debate and promote new ideas around organized crime. To do that would mean harnessing the available expertise, drawing in new sectors and seeking to financially support new actors, primarily in civil society. The GI-TOC structure – with a board, secretariat, a network of experts, senior advisors, and fund to support others – sought to provide an institutional framework through which this could occur.

After the February 2012 meeting, a steering group was appointed; seed funding was made available by the Norwegian government; premises were donated by the Swiss government for the secretariat in Geneva; and the launch of the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime was set for September 2013 in New York.

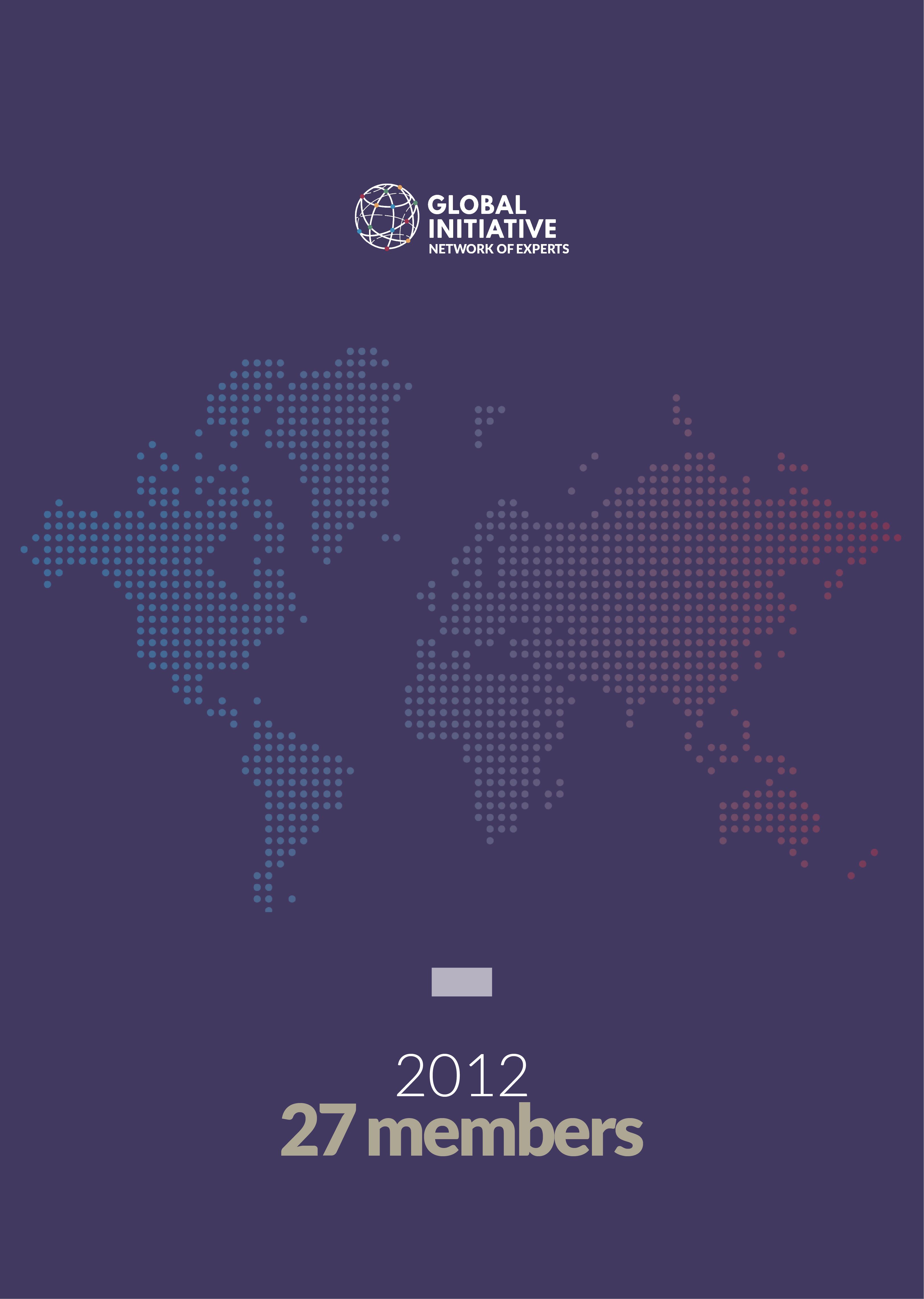

On 20 September in a UN conference room, the first general meeting of the Global Initiative Network was held to launch the organization. There were 120 participants, including the 27 founding members, who agreed to a constitution that defined the primary purposes of the new platform – a ‘network to counter networks’.

Mark Shaw was appointed director and a board was appointed, with Sarah Cliffe nominated as first chair of the board.

There was an urgent need to build more effective political consensus and mobilize a more strategic global approach to what had taken the form of an increasingly global threat to stability.

2013–2023

Laying the building blocks of a strategy against transnational organized crime.

The founding members of the newly constituted organization (now known as the Global Initiative Network of Experts) were united around the critical imperative of developing a more effective response to the manifold challenges of organized crime.

There was already strong evidence that there had been a surge in illicit markets since the era of rapid globalization in the 1990s and early 2000s. Meanwhile, new, diverse criminal economies were fast emerging, adding to the complexity of the challenges facing the newly minted organization. The costs of organized crime were mounting, and they were not only financial but also borne in terms of societal harms, including threats to human security, good governance, democratic values and environmental sustainability.

Finding an effective response to organized crime had long been part of the policy narrative, but it had become partly eclipsed by the prerogative of the war on terror, and in many cases politicized. Approaches to dealing with organized crime were also monofocal, with heavy reliance on law enforcement interventions, often with harmful human rights counter-effects in many contexts.

A decade ago, the GI-TOC came into existence to address these challenges and the shortcomings in the global response. It was clear to the founding members that a different policy mentality was needed, one that was not afraid to cross institutional boundaries by coupling the normative state toolkit of anti-crime responses with more comprehensive initiatives.

Debating these challenges, it was agreed that the organization’s mandate should be to put in place ‘the building blocks for a global strategy against organized crime’. It acknowledged that considerable work was required to reduce the impact of transnational organized crime, and that a multifaceted approach was needed.

To navigate the organization through its formative phase, a strategy was mapped out in dialogue with the founding members to guide its work and accomplish the administrative functions associated with any start-up, such as the legal registration of the entity, agreeing on a governance structure, branding and identity, and how to attract sustainable resourcing. An outreach programme was devised that would highlight the threat of organized crime and engage key external stakeholders. As part of this, the director and staff addressed several audiences that included ministerial, law enforcement, civil society and academic representatives.

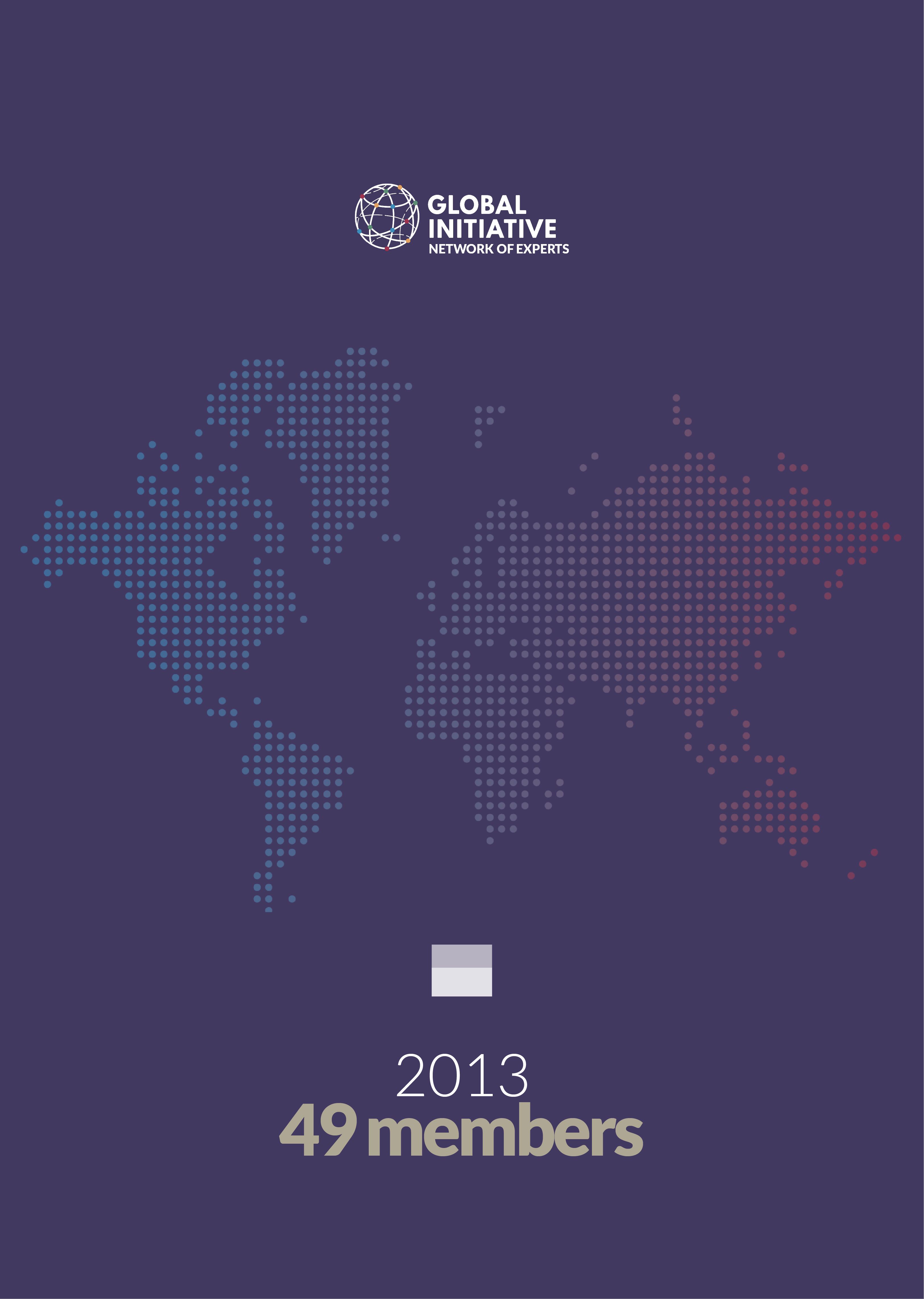

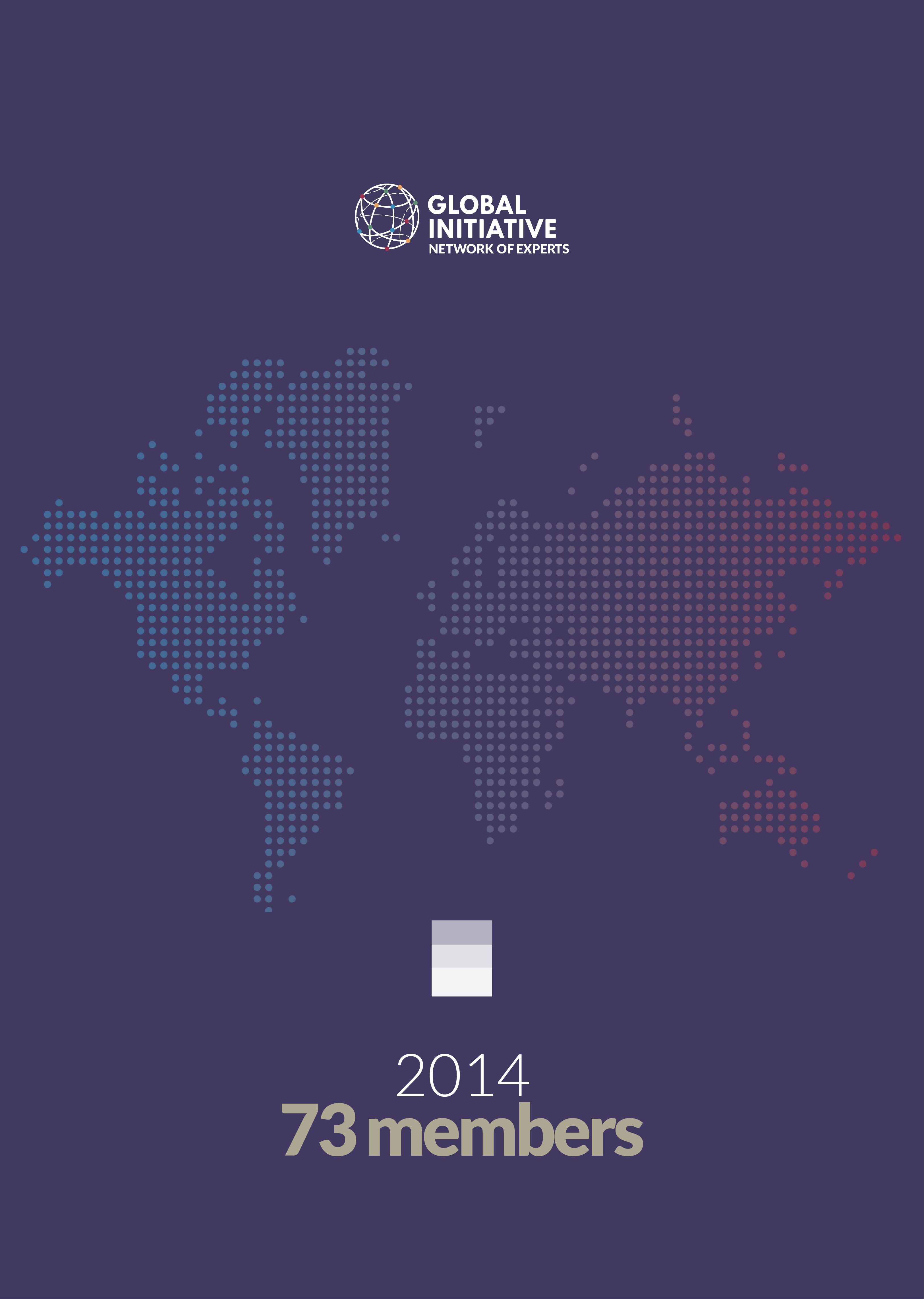

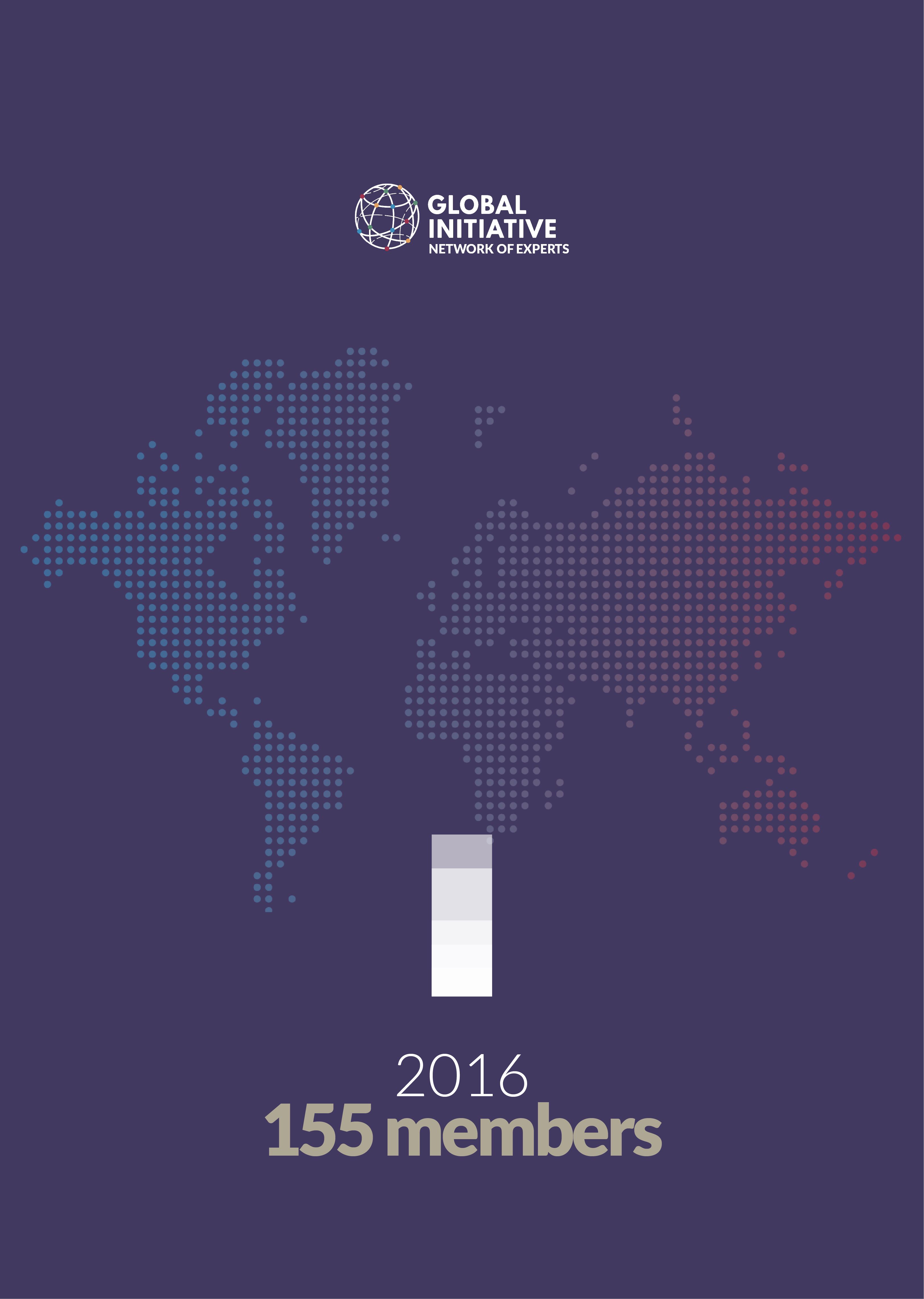

The core group of founding members was expanded to a network of 65 experts, collectively bringing to the young organization a broad range of thematic and geographic expertise. By 2015, the Network had grown to 100 members. Later, it was complemented by a board to provide fiduciary oversight and substantive advice to the secretariat. The director and secretariat report to the board and the Network approves the board’s membership. Today, the Global Initiative Network exceeds 600 members – it has expanded tenfold in ten years.

In its foundation phase, the organization’s catalytic work on migrant smuggling and human trafficking markets, environmental crime, cybercrime, drug trafficking and policy, and illicit financial flows brought recognition in the policymaking world and the media of the GI-TOC as a respected source of analysis and data on organized crime.

Exploring the role of development actors in countering organized crime and seeking ways in which development interventions could engage with the challenges of organized crime, the GI-TOC initiated the Development Dialogue in 2014. Now one of its flagship programmes, the Dialogue has become a leading policy forum, especially following the publication of a framework tool for analyzing organized crime as a development concern. Subsequently, through a number of avenues, the GI-TOC has continued to ensure that organized crime is an issue that is mainstreamed in the development debate.

2015 was a year in which some significant policy shifts changed the way that development actors would engage with organized crime programming. The GI-TOC participated in several events on the architecture of global organized crime as a development policy prerogative, and began to generate attention in government, among practitioners, civil society, academia and the media.

The same year, a three-year strategy document identified key focus areas aimed at establishing an effective and reputable global organization that was soundly governed and active in all regions, through the dissemination of expert analysis and by expanding the number and diversity of its Network of Experts. By 2017, all the objectives of the strategy had been met.

By 2016, with the Sustainable Development Goals approved – including a target dedicated to reducing illicit financial flows and arms flows, and to combat all forms of organized crime – the GI-TOC’s mandate had become increasingly pertinent. Several years later, it is evident that a great deal still needs to be done if the international community is to meet this target. It is the GI-TOC’s responsibility to help make it happen.

In 2018, the GI-TOC turned five. The organization had developed thematic and geographic approaches as part of its strategy, produced wide-ranging catalytic research, supported policy development, and piloted nuanced and creative responses to counter the threat that organized crime represents to human security and the integrity of states. Reflecting on those first five years, it is rewarding to see how the approach, set out in the founding document and subsequent strategies, had gained traction. The building blocks were being manoeuvred into place, and the architecture of the global strategy against organized crime was taking shape.

Over the next three years the strategic focus was on consolidating growth, and expanding the impact and reach of the organization. Among the strategic objectives set for the period 2018 to 2020 were to build the analytical evidence base for organized crime economies by establishing regional observatories to inform global responses commensurate to the threat; grow and diversify human resource capacity by expanding the Network and complement of expert staff in all regions; promote engagement, debate and discussion; and develop field-based programmes to withstand and respond to organized crime by improving resilience at the community level.

During this period, offices were registered in Vienna, Malta and South Africa, and observatories of criminal economies established in eastern and southern Africa, the Sahel and North Africa, and south-eastern Europe.

The Resilience Fund was launched in 2019, and the first index to analyze organized crime was published later that year.

Building resilience from the bottom up

In March 2019, with the support of the government of Norway, the GI-TOC established the Resilience Fund.

The Fund was conceived to provide financial support to individuals and community groups harmed by the effects of organized crime.

It equips beneficiaries with the financial means, capacity and skills-building tools to seek innovative approaches to citizen security and peacebuilding, and to help them adapt and respond to adversity.

The Fund has grown since its launch and now supports over a hundred grassroots beneficiaries in some 50 countries and has attracted new sources of funding.

Over the next few years, building on the foundation activities, the GI-TOC pursued its mandate as a global network in action, through a balanced programme of activities in the face of illicit markets that were becoming increasingly complex, digitalized and harmful.

During this period the organization increased the reach of its research, now disseminated in multi-lingual editions, to cover a wider range of geographic and topical areas, and increased the number of regional observatories of illicit economies and civil society to six, to enable truly global coverage.

Quantifying global criminality and resilience

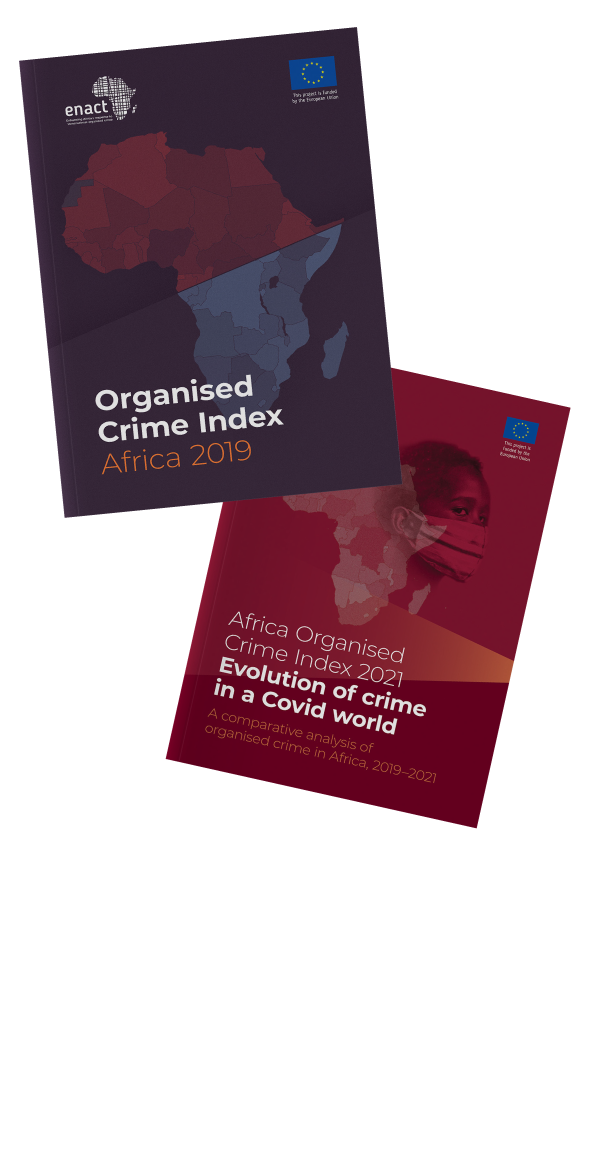

The ENACT Organised Crime Index Africa was launched in 2019 – the first tool of its kind to analyze organized crime – using a model that brings together the components of criminality and resilience for each country in Africa.

The findings provide a nuanced picture of criminal markets and actors, and resilience measures, thereby creating the foundational data and evidence base upon which policy responses can be developed in a more targeted way.

In 2021, we produced the first Global Organized Crime Index, the flagship research output of the GI-TOC, a multi-dimensional tool that assesses criminality and resilience for 193 countries.

The expanded 2023 iteration features several new key criminal markets and actors to provide a more comprehensive assessment of the global organized crime threat.

Meanwhile, there were global disruptors and macro challenges gathering on the horizon. Following restrictions on travel and convening imposed to control the spread of the coronavirus pandemic that had surfaced in late 2019, the GI-TOC adapted and realigned its activities. It invested in strengthening outreach and engagement through the web and social media platforms.

In February 2022, just as the world was emerging from the pandemic, war broke out in Europe. With the invasion of Ukraine, the organized crime landscape shifted again, bringing into perspective how, organized crime continues to be a cross-cutting, global threat to peace, development and democracy.

COVID

The pandemic brought into sharper relief a number of underlying trends that were already evident before the crisis. It created new opportunities, as well as some barriers, for organized crime.

The pandemic period was a challenging time for the GI-TOC, but in many ways a fruitful and productive one. The organization moved rapidly to investigate the pandemic’s impact on organized crime, and produced several analytical reports and newsletters, and a podcast series.

These attracted significant media coverage, expanded our audience basis and received positive stakeholder feedback. These efforts demonstrated organizational agility and responsiveness, highlighted our expertise and resulted in real impact for the organization.

In a context of conflict, geopolitical uncertainty and increasingly fragile coalitions, the organization’s work has continued to put in place the building blocks identified 10 years ago to achieve the founding mission:

to develop a coordinated global response to organized crime and increase resilience to it among vulnerable communities.

CHANGING THE PARADIGM

Next steps in a global strategy

Within a decade, the GI-TOC has developed dynamically from a small platform conceived by a group of experts committed to establishing a new ‘initiative’ to respond to organized crime. Those founding members met to articulate a vision for a more effective global response. At the time, it was difficult to envisage how effective we would be in delivering on that concept of a better way forward. However, over the last 10 years, our neutrality has allowed us to begin shaping many of the building blocks of a global response to transnational organized crime, by nurturing communities of resilience, expanding our network of expertise, and developing the Index of Organized Crime, among many other initiatives. And today we have grown into a globally influential, financially sustainable organization with over 100 full-time staff and consultants operating in 60 countries.

But it would be rash in the extreme not to recognize that the challenges remain. If anything, the spectre of organized crime is today more menacing than it was 10 years ago, all the more so as criminal economies cross-breed, prosper and mutate amid a polarized world order whose democratic pillars and principles of multilateral cooperation that have been largely taken for granted since 1945 are crumbling.

Inequality is at an all-time high, conflict and violence rumble on, climate change is wreaking untold, tangible damage by the day, many states and regions are becoming increasingly fragile, state sponsored corruption is a systemic mode of governance in many countries, and once utopian digital technology appears to have been let off its leash into the hands of cybercriminals. These are wide-reaching forces that shape the environment in which organized crime thrives, and have significant implications for response strategies.

As it enters its second decade, the GI-TOC will look to improve its capacity to catalyze more effective strategic responses to transnational organized crime and strengthen resilience. This means adapting and growing, while staying true to its origins as a ‘network to counter networks’ to help make the world safer from organized crime. For the 10th anniversary, we are engaging the Network, Board and staff to take stock of the organization’s first decade, highlight some of the achievements and undertake a process of strategic thinking on how to position the GI-TOC for its second decade. In so doing, we should remember that the GI-TOC was founded, as the only international, independent organization with a global mandate to formulate a strategy to reduce the global harms caused by organized crime and simultaneously build networks of resilience to it.

The GI-TOC intends to publish a report titled ‘Intersections: Towards a global strategy against transnational organized crime’, which will put forward a number of ideas on why such a strategy is needed and what it could contain, outlining what can be done differently, including new narratives and approaches – in short, how to change the paradigm.

It will underline the need for a whole-of-society approach and systems thinking to look at illicit economies. It also highlights the need for identifying points of intersection: between different criminal markets; linking transnational networks; connecting the upperworld and the underworld; and between organized crime and other global challenges such as climate change, armed conflicts, migration, sustainable development, and the risks associated with rapid technological change. These intersections are seldom clear vectors, distinct nodes or hotspots: most often they are blurred lines and grey zones where the licit meets the illicit. Understanding these intersection points will enable more effective prevention and remedial action to disrupt and degrade criminal networks.

2013-2023

A DECADE OF ACHIEVEMENT

Stay updated with the Global Initiative's activities by subscribing to our mailing lists.

Receive, via email, our open-source publications, tools, articles, events, and more updates about our projects.